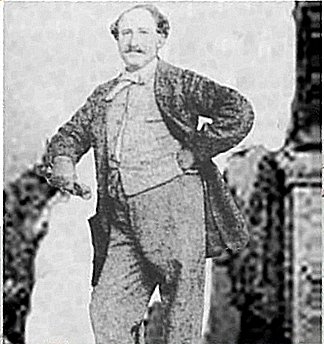

Joseph Osmond Barnard was born in Portsmouth, England in 1816. He arrived in Mauritius in 1838. A year later he married a young woman of Dutch origin. An advertisement in a local newspaper Le Cernéen of March 9, 1839 described Barnard as a miniature painter and engraver.

Although he had little experience in engraving miniature portraits, his attempts to engrave the Queen’s head were surprisingly successful. The one penny orange-red and the deep blue two pence, “Post Office” stamps engraved on copper plate by Barnard were put for sale on September 22, 1847.

Barnard died in 1865 at his Sugar Estate, purchased in 1862 near Grand Port.

Ruins of Vieux Grand Port Archeological Site

The Barnard Myth

The following are an extract from the Encyclopaedia of Rare and Famous Stamps by L. N. Williams published by David Feldman, Geneva

The description of Barnard as a watchmaker and jeweler persisted without question in philatelic literature from 1880 onwards – from The Stamp Collector by W.J. Hardy and E.D. Bacon London 1899 p 108, to Modern Stamp Collecting by Fred J. Melville London 1940 p 106, to ‘Post Office’ Mauritius, 1847 by Michael Harrison London 1947 p 27 to Stamps of Fame London 1949 p 23. E.B. Evans, though not infallible, and the editors of the official list of the Royal Philatelic Society London, were considered to be sufficiently careful in checking statements to be relied on as authorities.

However, it seems that all were in error. Peter Ibbotson under the title ’The Barnard Myth’ in Stamp Collecting, vol 123 p 527, 7 November 1974 and p 1087, 30 January 1975 – and also Harold Adolphe, Chief Archivist of Mauritius, the great help of whom Peter Ibbotson was to acknowledge, and Raymond d’Unienville under the title ‘The Life and Death of Joseph Osmond Barnard, Stowaway, Engraver, Stevedore and Planter’ in The London Philatelist vol 83 pp 263-265 December 1974 – published the fruits of research establishing that Barnard was born of probably Jewish parents named David and Rebecca, in Portsmouth on 10 August 1816. The Navy List of 1816 records a D. Barnard of Hanover Street, Hilsca, as a licensed Navy Agent for petty officers and seamen. Joseph Osmond Barnard, it is revealed emigrated to Mauritius as a stowaway aboard the three-masted ship Acasta, arriving at Port Louis on 6 December 1838 where until 1851 he was in business as an engraver and printer.

When conducting some research into certain Post Office Mauritius in 1977 I was in communication with P.J. Barnwell, a nonagenarian, sometime of the Royal College in Mauritius and longtime contributor to the Dictionary of Mauritian Biography. He wrote to me:

“It had not occurred me to question the usual statement of Barnard as being a watchmaker and jeweler. Europeans in Port Louis often turn their hand to various tasks, but I doubt if Barnard actually made any watches; watchmender is a more likely occupation. His marriage certificate described him as an engraver and miniature-painter. An advert of 1851 allied him with a man who was described as a watchmaker. When I was in Mauritius, and looked for his death I made a note of a planter, Joseph Osmond Barnard; and some years later, Noel Regnard found a wedding ‘act’ of a man with the same three names, described at that time as above stated. That he was a dealer in jewels as well as watches, and an engraver-painter, all allied trades, is easy to accept…”

The published research shows that from 1851 to 1862 he was in business as a partner in lighterage and shipping establishments; his marriage was to a Mauritian, the natural daughter of a resident, in September 1839. He died on 30 May 1865, leaving ten surviving children.

. Top

Another widely published statement about Barnard is that he was half-blind. It would be unjust to deduce from his engravings alone that his eyesight was anything but perfect, particularly having regard to the minuscule letters ‘J.B.’ engraved on the truncation of the neck of the effigy. However, there is substantial evidence that his sight was not all that he could have wished.

No instructions or invitation to tender have been found; probably the details of what he was to perform were conveyed to Barnard in a conversation. No written acceptance of the estimate has been found nor even the date when Barnard was instructed to carry out his work.

It is so highly improbable as to be discounted that the design was left to him alone, and the presumption must be that someone in authority gave him instructions, detailed instructions about what to engrave.

According to the article by Adolphe and d’Unienville:

“His instructions were that a profile to left of Queen Victoria with diadem should occupy the middle of each stamp, as it did on the English penny and two penny stamps.”

“He chose a small copper plate about 3 1/4 inches by 2 1/2 inches, such as might be used for printing a lady’s visiting card, on which to engrave the design.”

Although he had described himself in an advertisement in Le Cernéen the local newspaper, for 9 March 1839 as a Miniature Painter and Engraver it seems that he had but little experience of engraving portraits, at any rate, miniature portraits; his attempts to copy the noble lines of the Heath’s engraving of the Queen’s head were crude. Nevertheless, there is about the design a simple charm which has perhaps in no small measure contributed to the popularity of the Post Office Mauritius with collectors.

Barnard engraved the 1d. design in the north-west corner and the 2d. in the north-east corner of the small copper plate. No remarks have been called forth about the wording POSTAGE,. MAURITIUS, ONE PENNY, and POST.

However, a whole romance has been built up about the other word, OFFICE. There is no direct evidence to support the theory that inscribing OFFICE was an error. The argument in favor of its being an error is based, au fond, on the early statements in the philatelic press that it was an error, and on the undoubted fact that, within eight months, a new issue was put on sale with the word PAID inscribed on both values in the place where on the first issue the word OFFICE had appeared – moreover, there is no trace in the Mauritius archives of any reason for the change.

. Top

The argument against the ‘error’ theory is based on the equivalent of the legal maxim omnia praesumuntur rite et solemniter esse acta donec probetur in contrarium, which is that all things are presumed to have been done properly and with due formalities until it be proved to the contrary. The contra-errorists, of which I have been one for as long as I can recall having had an opinion on the subject, point first to the existence of postal markings inscribed POST OFFICE MAURITIUS or MAURITIUS POST OFFICE in use in the colony for many years before adhesive postage stamps were ever thought of there or, indeed long before they were brought into use in England. The first marking within an oval frame and reading COL/POST OFFICE /MAUIRITIUS came into use in 1834, but some eight years previously an unframed MAURITIUS/POST OFFICE had been used, and at least two other similarly worded markings were brought into use in 1832 and 1838.

Why should OFFICE be considered an error in relation to the 1847 issue of Mauritius? Echo answers Why?

The answer, purely and simply, would seem to be that, if it is regarded as an error, it opens the door to romantic imaginings. There can be little doubt that it did so in the case of Dr Georges Brunel, an enthusiastic, if not notoriously factual, writer on all matters philatelic, who was provided with an opportunity to give rein to his imaginations in 1920 when Theodore Champion had to pay what was then a record sum for not only a Post Office Mauritius but any stamp, namely, 116,912 francs (£2,248) at auction of the Mors collection to secure a Two Pence Post Office Mauritius for his own collection.

Champion was a French dealer who had a remarkable collection of great rarities. He engaged Dr. Brunel to write the story of the Mauritius stamps. Of course, Dr. Brunel was aware of at least some of the earlier writings and, certainly, any he lacked and wished to refer to would have been provided. However, he seized the opportunity of adding glamour to the round unvarnished tale of the earlier writers imagined error. It makes a readable story as presented in Bulletin Mensuel de la Maison Theodore Champion et Co for June and July 1920 and translated and abstracted by, W. Renouf in The Philatelic Journal of India, vol 25 pp 80-83, June 1921 from which I shall cite.

The skeleton of imagined fact had to be rounded out with the flesh of imagined reconstruction of the circumstances. ‘The error in the plates of Post Paid stamps’ error had been nailed beyond recall by the discovery some eight years earlier, as will be mentioned, of Barnard’s engraved plate for the Post Office Mauritius, so Brunel gave the error story a twist.

The secret of the rarity of the ‘Post Office Mauritius’ is that it was a blunder. But philately has benefited thereby and this exemplifies how good can come out of evil.

We now see our friend Barnard with an order to engrave the Mauritius stamps. The design of the profile of the head of Queen Victoria has been approved, and he has been given verbal instructions as to the inscriptions. He has touched his forehead with his fingers to signify that he has grasped what is wanted.

He sits to work. As he is really a jeweler and not an engraver, the result must not be criticized too severely. It is passable. He inscribes the word ‘Postage’ at the top in burly letters, the value at the foot, and Mauritius to the right. Only one side remains blank, but here he experiences a tragic lapse of memory. His sketch gives no assistance, and for the life of him he cannot recall the words which he has to engrave. He sets out to find the Postmaster Brownrigg, to ask him to refresh his memory. Arriving at the door of the Post Office he sees the words Post Office before his eyes. It is born upon him that these are the missing words. Delighted, he rubs his hands together, he does a right about turn, and finishes his engraving forthwith. And incidentally he perpetrates the most colossal and the most famous error in philately.

He is so pleased with the result that he does not trouble to submit proofs. He prints 700 copies, 350 in red (1d) and 350 in blue (2d). Then he takes these to the Governor.

‘Triple sot’ (we had best not attempt a translation) burst from the representative of the Britannic Majesty when he read on the stamps, ’Post Office’ instead of ‘Post Paid’. However, the mistake had been made. The stamps might as well be used. The Governor was about to give his annual party, and he used the majority of the issue on the invitation cards for this party.